<Image http://www.flickr.com/photos/hanuman/1860273153/>

No doubt most of you will have read the (unintentionally hilarious) interview with Udacity founder and the media's poster child for MOOCs, Sebastian Thrun. If you haven't the short version (minus the ego fanning and competitive cycling) is that Thrun has realised that not many people complete MOOCs, and that making them pay is a good incentiviser, so he's making Udacity an elearning corporate training company.

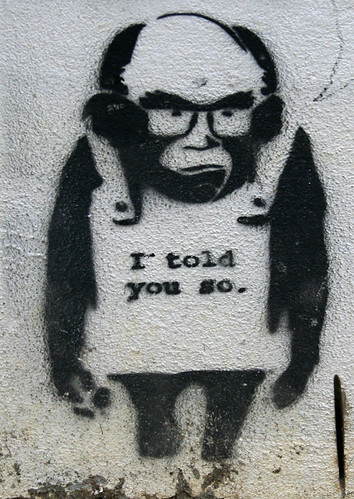

And there it is. After all that hype. All that "Napsterisation of higher education", the "end of universities", the "10 global providers of education" nonsense, what do we have? A corporate elearning company. As TS Eliot observed, the world ends not with a bang, but a whimper.

Everyone will blog about it (I expect there will be a wave of "the end of MOOCs" pieces by the very people who wrote "the end of universities" ones), and I can barely bring myself to add to the noise, but if you take a step back, it really is a fascinating, and telling case study in what happens when companies try to do openness.

What is both interesting and depressing about it is the sheer predictability of it all. I commented a while back that FlatWorld Publishing provided a good warning. When the going gets tough, openness is the first casualty. Only last week George Siemens was railing against how people had opted for the easy option because openness was complex and messy. Thrun says it's because he is worried that the Udacity product was 'lousy', but you can bet those venture capitalists were whispering in his ear "where is the return on our investment?".

A couple of points worth noting: Thrun seems to have 'discovered' that open access, distance education students struggle to complete. I don't want to sound churlish here, but hey, the OU has known this for 40 years. It's why it spends a lot of money developing courses that have guidance and support built into the material, and also on a comprehensive support package, ranging from tutors, helpdesk, regional study centres and so on. But of course, none of the journalists and certainly not the new, revolutionary people at Udacity wanted to hear any of this. They could solve it all, and why hadn't higher education thought of this before? As Audrey Watters said to me on twitter:

@mweller "disruptive innovation" means never having to say 1) you're sorry 2) you're wrong 3) you're ignorant 4) all of the above

— Audrey Watters (@audreywatters) November 14, 2013

(Audrey has an excellent post on the Thrun interview that you should read)

I also like the way the article depicts Thrun as bravely digging into the data: "he was obsessing over a data point that was rarely mentioned in the breathless accounts about the power of new forms of free online education: the shockingly low number of students who actually finish the classes". That's right, no-one had noticed. If only someone had, say, plotted all of the MOOC completion data...

Anyway, where does this leave us? Does it mean MOOCs are dead? Not really. It just means they aren't the massive world revolution none of us thought they were anyway. And it also suggests that universities, far from being swept away by MOOCs, are in fact the home of MOOCs. You see, MOOCs make sense as an adjunct to university business, they don't really make sense as a stand alone offering. One wonders if the likes of Shirky will be writing about how wonderful the university model of open education is. So in the end, far from being a portent of doom of the university model, MOOCs are a validation of universities and their robustness.

It's not the end of MOOCs, they just make more sense when you view them as part of the OER continuum. Actually I don't think Udacity's product is lousy - they have some really fine open material. It's their business model that's lousy. To quote the Smiths song of the title: "Nothing's changed, I still love you, only slightly less than I used to."